![]() Cand eram in scoala generala mergeam sambata dimineata la cercul de literatura si pe drum ma gandeam adesea cum ar fi fost sa traiesc intr-o alta epoca, sa port corset si rochii voluminoase. Cred ca ar fi fost frumos… Astazi ma mai visez asa doar cand vad vreun film sau citesc vreo carte in care actiunea se petrece pe la 1800. O ocazie recenta cand m-am visat in rochii voluminoase a reprezentat-o vizita la muzeul Victoria & Albert din Londra. Acum cum am promis, revin acum cu partea a doua si va arat mai jos ce am vazut si citit despre istoria modei de la 1750 pana in 1910. Continuarea o gasiti aici.

Cand eram in scoala generala mergeam sambata dimineata la cercul de literatura si pe drum ma gandeam adesea cum ar fi fost sa traiesc intr-o alta epoca, sa port corset si rochii voluminoase. Cred ca ar fi fost frumos… Astazi ma mai visez asa doar cand vad vreun film sau citesc vreo carte in care actiunea se petrece pe la 1800. O ocazie recenta cand m-am visat in rochii voluminoase a reprezentat-o vizita la muzeul Victoria & Albert din Londra. Acum cum am promis, revin acum cu partea a doua si va arat mai jos ce am vazut si citit despre istoria modei de la 1750 pana in 1910. Continuarea o gasiti aici.

![]() Back in elementary school I attended literature classes on Saturday morning and on my way to the location I dreamed myself living in another century, wearing corset and voluminous dresses. That would be so amazing! Today I only dream myself like that when I see a movie or I read a book related to the late 18th century or the beginning of the 19th century. A recent opportunity when I dreamed myself like this was when I visited Victoria & Albert museum in London. As I promised, I’m coming back with the second part (or the first, is you want to take this journey chronologically). You can see below what I read and saw related to fashion history from 1750 to 1910. The story is continued here. Enjoy!

Back in elementary school I attended literature classes on Saturday morning and on my way to the location I dreamed myself living in another century, wearing corset and voluminous dresses. That would be so amazing! Today I only dream myself like that when I see a movie or I read a book related to the late 18th century or the beginning of the 19th century. A recent opportunity when I dreamed myself like this was when I visited Victoria & Albert museum in London. As I promised, I’m coming back with the second part (or the first, is you want to take this journey chronologically). You can see below what I read and saw related to fashion history from 1750 to 1910. The story is continued here. Enjoy!

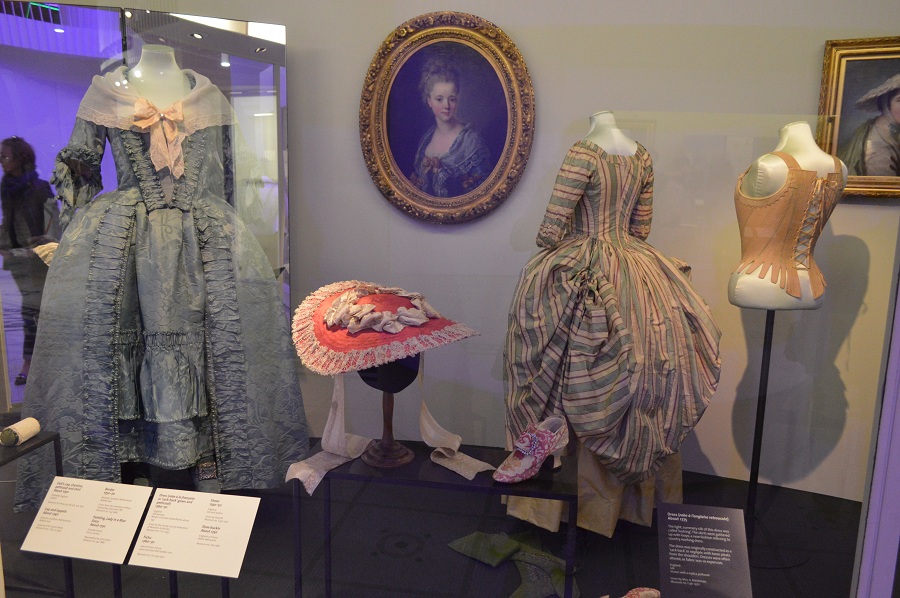

Court and Country (1750-1800)

Court fashion in the 18th century was characterized by the use of extravagant and exclusive silk textiles. French silks were highly sought-after until their import to Britain was banned in 1766. Designers and weavers in London also produced high quality silks, their exquisite patterns often based on English flowers. Mantua makers (dressmakers) made fashion dolls as a way of spreading information about the latest styles. Fashion plates were also circulated with depictions of what people were wearing at court. Away from London society –at home and at work –men and women wore practical clothes of wool, linen and cotton. Printed cottons, with their fast, bright colors became increasingly popular as new technology made them more affordable.

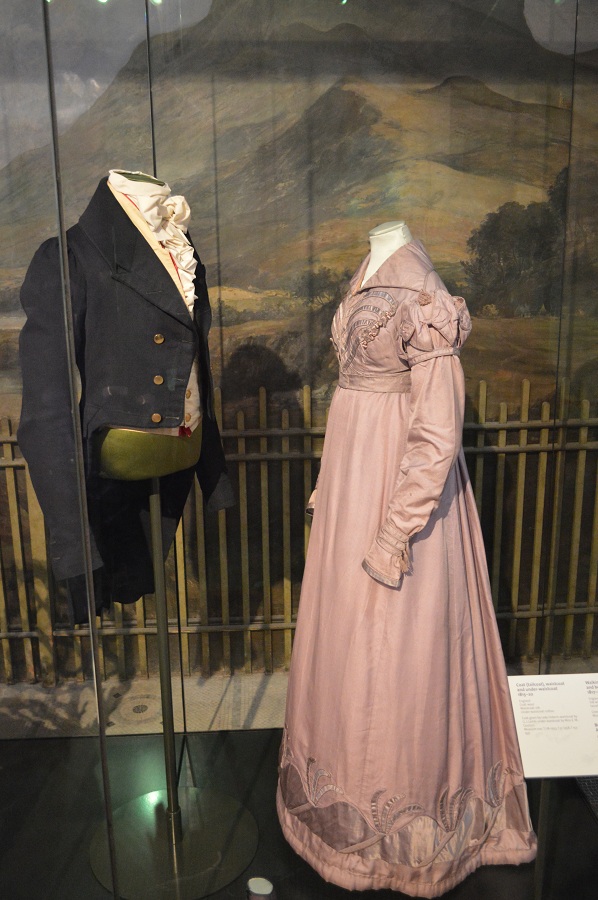

In Society (1810-1830)

The high-waisted styles inspired by classical dress remained popular for the first part of the 19th century. Delicate fans were carried as accessories, while woven cashmere shawls in the Indian style were both decorative and practical. Evening dresses in the 1820s were often made of colored silk or the newly invented machine-made net. Dresses for grand occasions incorporated trimmings of the gold tinsel or embroidery, emphasizing the bodice and skirt hem. In times of mourning, women wore dull black silk crepe, but after a few months they could choose velvet trimmed with satin for evening wear. Normally, men wore tailored wool coats and breeches or pantaloons, with a crispy laundered, carefully tied neck-cloth. But some royal events still required old fashioned, embroidered court dress, including swords and wigs.

At Home (1830-1840)

These were years of great change. The first passenger railway opened in 1830, and in 1833 slavery was abolished in the British Empire. In the textile industry, the jacquard loom reduced labor costs and increased productivity. Innovation in the dyeing and fabric printing industry created choice for women and speeded up the pace of fashion. Women’s dress became increasingly voluminous, with balloon-like sleeves and full skirts. Feather-filled sleeve supports and petticoats stiffened with cord or horsehair were used to create the correct silhouette. Whitework pelerines (large collars) were fashionable for indoor wear. Magazines circulated information about the latest styles from Paris and London. Fashion plates presented images of the feminine ideal.

The Male Wardrobe (1840 -1860)

As women’s dress became increasingly elaborate, men’s formal clothing became dark and plain. A gentleman could, however, display his individuality and taste with a brightly patterned ‘fancy’ waistcoat. Either bought from an outfitter or hand-embroidered by his wife or daughter. But fashion was no longer the propagative of the upper classes. With the expansion of the ready-made tailoring trade, many more men could buy stylish clothes at competitive prices. The ‘Wellington Surtout’ (a type of overcoat) was recommended ‘to all who desire quiet, elegant, gentlemanly appearance’. City workers attempting to achieve gently through dress were known as ‘Gents’ or ‘swells’. They wore frock coats and top hats and carried carefully chosen accessories, such as canes and snuff boxes.

Fashion and Industry (1850-1870)

In the 19th century fashion benefited from advances in technology. The development of spring steel led to the invention of the ‘cage crinoline’. This frame of light, strong steel wire replaced heavy layers of petticoats and women’s dress became even more voluminous. Although ridiculed by the press, crinolines were very popular and produced in their thousands. Research and development in the chemical industry led to the discovery of artificial dyes. Women’s dresses were the perfect advertisement for these brilliant colors but aniline dyes could be hazardous. In 1869 the British Medical journal warned of the dangers of arsenic in magenta dye. It could leak out in washing, rain or perspiration. Visitors of the International Exhibitions in London in 1851 and 1862 could see high quality French luxury goods and fashions. These were regarded as the height of the good taste. By contrast, a French visitor to London found women’s dress’ loud and overcharged with ornament’.

Couture and Commerce (1870-1910)

The fashion trade was increasingly international with top couturiers such as Worth and Pingat attracting clients from all over the Europe and America. Couture houses produced exquisitely made clothes using superb silks, furs, lace and embroidery. Dressmakers and department stores copied the latest fashions. Shopping became an activity enjoyed by the people at all levels of society. Many garments could be bought ready-made, including corsets and the different types of bustles required to achieve the fashionable silhouette. Artists and dress reformers reacted against the artificiality of fashion. Instead, they created simpler styles using naturally dyed fabrics and made flexible garments of wool jersey for sports such as tennis. By 1900 these alternative styles had entered mainstream fashion.